First, read Daniel's concluding two paragraphs (although I urge you to read his whole piece - considerably shorter than my response - here):

While it's clear that much of 20th century classical musical life can be characterized by the active rejection of new composition in favor of the interpretation of older work, we desperately need some smarter ideas about the ways in which repertoires integrate or reject innovation, and perhaps we can get some ideas from religious and literary scholarship about the ways in which communities for whom the canon has been closed still maintain a creative life.Although I agree with some of your observations, I cannot agree with your conclusion. I think classical music is quite dead. It's easy to overlook this fact because many people still enjoy listening to it and there are many healthy organizations providing performances and recordings. I would argue that's not enough for the music itself to be "living".

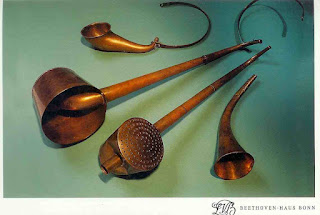

We still understand very little about the impact of the various technologies for "fixing" a music -- from oral transmission, to notation, and onto sound recording in its changing modes of exchange. A bit of music may or may not have some platonic ideal behind it which these various technologies reproduce to a greater or lesser degree of accuracy, but these technologies raise all sorts of questions about both liveliness and morbidity and further questions about how to distinguish between these two states in an environment in which a parasitic attachment to past liveliness is -- for better or worse -- a substitute for getting on with real change.

Classical music has had defined, unchanging, largely immovable boundaries for many decades. Allowable performance practices have a small acceptable range. When you talk about "classical music" I, and everyone, know exactly what you are referring to. Since the advent of authentic baroque and renaissance performance decades ago not much has changed. Oh, there's more flash and more marketing these days. "Classical" music isn't changing. There's a lot of "new" music asking to be let in. The audiences are not terribly thrilled by it. Chilled would be a better description. Exceptions are so rare you cannot claim they are a revitalizing influence.

You point out that an active academia codifies the practice. Absolutely. Music schools are filled with people who have devoted their lives to finding newer and newer things about a fixed body of knowledge. They teach the "proper" way of playing. Teachers and students may know history but they are still being forced to repeat it.

You point out that other parts of the world have growing classical music "scenes". Doesn't this mean that people are still finding the meaning and elegance which the classics has always provided to anyone who cares to partake? More cynically, it also might mean that other societies are attempting to find some equality with the European musical homeland. There is still class distinction in classical music.

Of course composers continue to suggest paths for a possible future of classical music. They (we) attempt mostly to evolve from what was there before. The performing and recording companies promote a painfully small subsection of these possibilities, based, in my opinion, more on importance than on talent. But few pieces have been accepted by the general audience. Most of the audience prefer to pay to hear their old friends Beethoven or Schumann or Wagner or Brahms again and again. And it's not clear if any of the new "pledges" to the composer pantheon will be allowed to really join the "fraternity". Who since Bartok has really been awarded decades of repeated performances?

I suggest that we would be better off to accept that musics have lifespans - they come and go, they are born, they flower and then they die. We can still enjoy the dead ones, preserved for us in elegant museum-like concert halls. But the formative, creative, socially relevant periods of dead musics have passed. We can honor the fact that they've had a huge influence on our culture and provided great beauty and meaning and challenges to anyone who cares to take advantage of them. As a culture we have concluded that these musics should be preserved and that knowing them is an essential experience of our time. So is experiencing Shakespeare, but I hope no one would suggest Elizabethan theater is not dead.

We should all look to the future with the realization that something new is coming, something that will reflect our present without a restrictive obeisance to the past, something that will mirror the hopes and dreams and fears of a whole lot of living people, who will anxiously wait to find out if their most wonderful dreams or most horrible fears come to pass, who don't have much time to think about music but will know absolutely which organized sounds resonate with their thoughts and hopes and feelings. And which don't.

Those of us who appreciate and revere what came before may not like the new stuff. That's too bad, but there's nothing forcing us to listen to anything in particular. Everyone seems to listen to something. And everyone seems to know what they like.

Finally, the search for new metaphors to describe the death or life of this or that music is itself a living art. Newer and stranger comparisons and analogies are regularly found to prove the same points over and over. The problem is that any music - whether classical, jazz, rock, hip-hop, take your pick - encompasses a vast sweep of society, a long history and varied aspects of culture as to be indescribable as a whole in any simple manner. You could say classical music is an elephant beset by countless blind men and women, each trying to describe their small corner of the beast and each finding a unique descriptor. Yes, that's another metaphor. Oops, I did it again.

Other Mixed Meters attacks on Classical Music's mortality (plus teaser quotes):

If Music Be The Food of Love "Hip Hop, as the magazine cover says, is not dead. However Hip Hop has recently discovered its own mortality."

A New Rhapsody in Blue "It occurred to me that if many (or even a few) performances of classical music had this level of creativity in them - of even a small fraction of the creativity in this performance - I would not think of it as such a dead art form."

Everybody Loves Beethoven (Probably) "it is probable that 98% of all Americans these days don't know any contemporary composers at all, and if they did - unlike in Mencken's hypothesis - their reaction to finding out about them would be the shrugging of shoulders and the changing of channels."

Classical Music Isn't Dead, It Just Needs a Rest "I conclude that in such situations the music is not meant to offer a contemporary perspective. They have other forms of art for that. I fear this music is more like a spa treatment for ones ears."

Could Terry Riley's In C be Accepted As Classical Music? "Yes, getting this piece into the standard repertory is a long ways off. If it happened, In C would change from a "minimalist classic" into an actual piece of classical music. That would provide strong evidence that classical music has some life left in it."

Lifespan Tags: classical music. . . death of classical music. . . concert halls are museums